37 - Afra-descendant Literature

- Carolina Quiroga-Stultz

- 26 feb 2021

- 23 Min. de lectura

Marina is a young woman who knows how to harbor fragrances on her skin. But her divine gift is desired by and resented by those who cannot cage her. In the comments we talked about how religious and political systems redefined the role of women and minorities in Latin America.

First Story

The Revenge of the Mermaids

Because they could not save Persephone from the abduction of Hades, the Oceanids (that is sea nymphs) were punished. They were turned into terrible animals, half woman, half fish. Poor nymphs, what were they going to do against such a sinister god? But now that they were monsters, they had power.

If men fall prey to their songs, they eat them. In the end, we all got to eat something. But the Mermaids' plan was different. The plan was to save all women from men's abductions, and to stop them from coming with their ships to kidnap them, and to subject them to the terrible captivity of home-life. In truth, the sirens fulfilled the duties that the nymphs could not.

In doing so, they answered Persephone's secret prayers.

(From the website Círculo de Poesía, Revista Electrónica de Literatura: (text in Spanish): https://circulodepoesia.com/2010/11/microcuentos-de-mayra-santos/

Translated from Spanish by Carolina Quiroga-Stultz, reviewed by Don Hymel.)

Welcome

Welcome to Tres Cuentos, the podcast dedicated to literary narratives of Latin America. The short story written by the Puerto Rican author Mayra Santos-Febres can be found in Spanish on the website Círculo de Poesía. The link to the site is in the transcripts.

*

Initially, I found Mayra Santos-Febres in the book Afro-Puerto Ricans in the Short Story, An Anthology, edited by Victor C. Simpson. I knew I had to present her story “Marina’s Fragrance.”

After trying to contact the Spanish publisher for permission to feature the story in the podcast, my next move was to reach the author. I called the National Library of Puerto Rico. I thought librarians could help you find a needle in a haystack. Unfortunately, due to COVID-19, no one was working.

Feeling that I might have to go with a different author, my stubborn mind tried two more attempts. I called the University of Puerto Rico and later the National Foundation for the Popular Culture.

In this last one, a nice man answered. I explained what I needed, and he provided me a phone number. Yet, he was not sure if it would work. It did, and I am pleased to say that we were granted permission to present the story and were able to interview the author.

Thus, with the Afra-Puerto Rican writer Mayra Santos-Febres, we finalize our journey through afro descendants' literature.

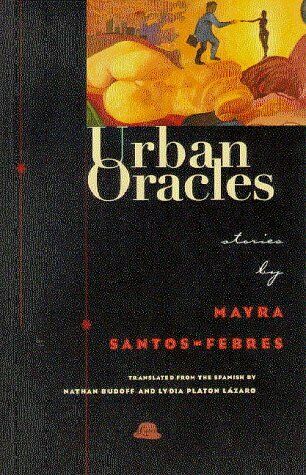

The following story can be found in the book Urban Oracles: stories by Mayra Santos Febres, translated by Nathan Budoff & Lydia Platon Lázaro, published by Brookline Books, Inc.

The story, Marina’s Fragrance, comes in the voice of storyteller Diane MacKlin, and I will tell you more about her in the comments.

Mayra Santos-Febres tells us the story of Marina, a young woman who knows how to harbor fragrances in her flesh. In time her feelings equal the scents her body remembers. But her divine gift is desired by and resented by those who cannot cage her.

Story

From Urban Oracles: stories by Mayra Santos Febres, translated by Nathan Budoff &Lydia Platon Lázaro. Copyright © 1997 by Brookline Books, Inc. Used with permission of translator Nathan Budoff. All rights reserved.

Marina’s Fragrance

By Mayra Santos Febres

Narrated and adapted Diane Macklin

Doña Marina Paris was a woman of many charms. At forty-nine her skin still breathed those fragrances which, when she was young, had left the men of her town captivated and searching for ways to lick her flanks to see if they tasted as good as they smelled. And every day they smelled of something different. At times, a delicate aroma of oregano brujo would drift out of the folds of her thighs; other days, she perfumed the air with masculine mahogany or with small wild lemons. But most of the time she exuded pure satisfaction.

From the time she was very little, Doña Marina had worked in the Pinchimoja take-out restaurant, an establishment opened in the growing town of Carolina by her father Esteban Paris. Previously, Esteban had been a virtuoso clarinetist, a road builder, and a molasses sampler for the Victoria Sugarcane Plantation. His common-law wife, Edovina Vera, was the granddaughter of one Pancracia Hernandez, a Spanish shopkeeper fallen on hard times, for whom time had set a trap in the form of a black man from Canovanas. He showed her what it meant to really enjoy a man’s company, after she had lost faith in almost everything, including God.

*

Marina grew up in the Pinchimoja. Mama Edovina, who gave birth to another sister every year, entrusted Marina with the restaurant and made her responsible for watching Maria, the half-crazy woman who helped Mama move the giant pots of rice and beans, the pots of tinapa in sauce, of chicken soup, roasted sweet potato, and salt cod with raisins, the specialty of the house. Her special task was to make sure that Maria didn´t cook with coconut oil. Someone had to protect the restaurant’s reputation and keep people from thinking that the owners were a crowd of blacks from Loiza.

From eight to thirteen years of age, Marina exuded spicy, salty, and sweet odors from all the hinges of her flesh. And since she was always enveloped in her fragrances, Marina didn’t even notice that they were bewitching every man who passed close to her. Her pompous smile, her kinky curls hidden in braids or kerchiefs, her high cheekbones, and the scent of the day drew happiness from even the most decrepit sugarcane-cutter, from the skinniest road-worker burnt by the sun, from her father, the frustrated clarinetist, who rose from his stupor of alcohol and daydreams to stand near his Marina just to smell her as she passed by.

Eventually, the effect Marina had on men began to preoccupy mama Edovina. She was especially worried by the way she was able to stir Esteban from his alcoholic’s chair. The rest of the time he sat prostrate from five o’clock every morning, when he finished buying sacks of rice and plantains from the supplier who drove by in his cart on the way down to the Nueva Esperanza market.

Marina was thirteen, a dangerous age. So, one day mama Edovina opened a bottle of Cristopher Columbus Rum from Mayaguez, set it next to her partner’s chair, and went to look for Marina in the kitchen, where she was peeling sweet potatoes and plantains.

“Today you begin working for the Velazquez. They’ll give you food, new clothes, and Doña Georgina’s house is near to school.” Mama Edovina took Marina out the back of the Pinchimoja over towards Jose de Diego Street. They crossed behind Alberti’s pharmacy to the house of Doña Georgina, a rich and pious white woman, whose passion for cassava stewed with shrimp was known throughout the town.

*

It was at about this time that Marina began to smell like the ocean. She would visit her parents every weekend. Esteban, a bit more pickled each time, reached the point where he no longer recognized her, for he became confused thinking that she would smell like the daily specials. When Marina arrived perfumed with the red snapper or shrimp that they ate regularly in the elegant mansion, her father took another drag from the bottle which rested by his chair and lost himself in memories of his passion for the clarinet.

The Pinchimoja no longer attracted the people that it used to. It had lapsed into the category of breakfast joint; you could eat funche there, or corn fritters with white cheese, coffee, and stew. The office workers and roadbuilders had moved to a different take-out restaurant with a new attraction that could replace the dark body of the thirteen-year-old redolent with flavorful odors –a jukebox which at lunch time played Felipe Rodriguez, Perez Prado, and Benny More’s Big Band.

*

It was in the Velazquez house that Marina became aware of her remarkable capacity to harbor fragrances in her flesh.

She had to get up before five every morning so she could prepare the rice and beans and their accompaniments; this was the condition imposed by the Velazquez in exchange for allowing her to attend the public school.

One day, while she was thinking about the food that she had to prepare the next morning, she caught her body smelling like the menu. Her elbows smelled like fresh recaillo; her armpits smelled like garlic, onions, and red pepper; her forearms like roasted sweet potato with butter; the space between her flowering breasts like pork loin fried in onions; and further down like grainy white rice, just the way her rice always came out.

From then on, she imposed a regimen of drawing remembered scents from her body. The aromas of herbs came easily. Marjoram and mint were her favorites. Once she felt satisfied with the results of these experiments, Marina began to experiment with emotional scents.

One day she tried to imagine the fragrance of sadness. She thought long and hard of the day Mama Edovina sent her to live in the Velazquez household. She thought of Esteban, her father, sitting in his chair imagining what his life could have been as a clarinetist in the mambo bands or in Cesar Concepcion’s combo.

Immediately an odor of mangrove swamps and sweaty sheets, a smell somewhere between rancid and sweet, began to waft from her body. Then she worked on the smells of solitude and desire.

Although she could draw those aromas from her own flesh, the exercise left her exhausted; it was too much work. Instead, she began to collect odors from her employers, from neighbors near the Velazquez house, from servants who lived in the little rooms off the courtyard of hens, and from the clothesline where Doña Georgina’s son hung his underwear.

*

Marina didn’t like Hipolito Velazquez junior, at all. She had surprised him once in the bathroom masturbating, which gave off an odor of oatmeal and sweet rust. This was the same smell (a bit more acid) which his underpants dispelled just before being washed.

He was six years older than she, sickly and yellow, with emaciated legs and without even an ounce of a bottom. “Esculapio” she called him quietly when she saw him passing, smiling as always with those high cheekbones of a presumptuous Negress.

The gossips around town recounted that the boy spent almost every night in the Tumbabrazos neighborhood, looking for mulatta girls upon whom he could “do damage.” He was enchanted by dark flesh.

At times, Hipolito looked at Marina with a certain eagerness. Once he even insinuated that they should make love, but Marina turned him down. He looked so ugly to her, so weak and foolish, that just imagining Hipolito laying a finger on her body, she began to smell like rotten fish, and she felt sick.

*

After a year and a half of living with the Velazques, Marina began to take note of the men around town. At Carolina’s annual town fair that year, she met Eladio Salaman, who with one long smell left her madly in love. He had a lazy gaze, and his body was tight and fibrous as the sweetheart of a sugarcane. His reddish skin reminded her of the tops of the mahogany tables in the Velazquez house. When Eladio Salaman drew close to Marina that night, he arrived with a tidal wave of new fragrances that left her enraptured for hours, while he led her by the arm all around the town square.

The ground of the rain forest, mint leaves sprinkled with dew, a brand-new washbasin, morning ocean spray… Marina began to practice the most difficult odors to see if she could invoke Eladio Salaman’s. This effort drew her attention away from all her other duties, and at times she inadvertently served her employers dishes that had the wrong fragrances.

One afternoon the shrimp and cassava come out smelling like pork chops with vegetables. Another day, the rice with pigeon peas perfumed the air with the aroma of greens and salt cod. The crisis reached such extremes that a potato casserole came out of the oven smelling exactly like the Velazquez boy’s underpants. They had to call a doctor, for everyone in the house who ate that day vomited until they coughed up nothing but bile. They believed they had suffered severe food poisoning.

Marina realized that the only way to control her fascination with Eladio was to see him again. Secretly she searched for him on all the town’s corners, using her sense of smell, until two days later she found him sitting in front of the Serceda Theater drinking a soda.

That afternoon, Marina invented an excuse, and did not return to the house in time to prepare lunch. Later she ran home in time to cook dinner, which was the most flavorful meal that was ever eaten in the Velazquez dining room throughout the whole history of the town, for it smelled of love and Eladio Salaman’s sweet body.

*

One afternoon, while strolling through the neighborhood, Hipolito saw the two of them, Marina and Eladio, hand in hand, smiling and entwined in each other’s aromas. He remembered how the dark woman had rejected him and now he found her lost in the caresses of that black sugarcane cutter. He waited for the appropriate moment and went to speak with his esteemed mother. Who knows what Hipolito told her –but when Marina arrived back at the house, Doña Georgina was furious.

“Indecent, evil, stinking black woman.”

And Mama Edovina was forced to intervene to convince the mistress not to throw her daughter out. Doña Georgina agreed, but only on the condition that Marina take a cut in her wages and an increase in her supervision. Marina couldn’t go to the market unaccompanied, she couldn’t stroll on the town square during the week, and she could only communicate with Eladio through messages.

Those were terrible days. Marina couldn’t sleep; she couldn’t work. Her vast memory of smells disappeared in one fell swoop. The food she prepared came out insipid –all of it smelled like an empty chest of drawers. This caused Doña Georgina to redouble her insults. “Conniving little thing, Jezebel, polecat.”

*

One afternoon Marina decided she wouldn’t take any more. She decided to summon Eladio through her scent, one that she had made in a measured and defined way and shown to him one day of kisses in the untilled back lots of the sugar plantation. “This is my fragrance,” Marina had told him. “Remember it well.” And Eladio, fascinated, drank it so completely that Marina’s fragrance would be absorbed into his skin like a tattoo.

Marina studied the direction of the wind carefully. She opened the windows of the mansion and prepared to perfume the whole town with herself. Immediately the stray dogs began to howl, and the citizens rushed hurriedly through the streets, for they thought they were producing that smell of frightened bromeliads and burning saliva.

Two blocks down the street, Eladio, who was talking to some friends, recognized the aroma; he excused himself and ran to see Marina. But as they kissed, the Velazquez boy broke in on them and, insulting him all the way, threw Eladio out of the house.

As soon as the door was closed, Hipolito proposition to Marina that if she let him touch her breasts, he would maintain their secret and not say anything to his mother. “You can keep your job and escape Mama’s insults, too,” he told her, approaching her.

Marina became so infuriated that she couldn’t control her body. From all of her pores wafted a scaly odor mixed with the stench of burned oil and acid used for cleaning engines. The odor was so intense that Hipolito had to lean on the living room’s big colonial sofa with the medallions, overwhelmed by a wave of dizziness. He felt as if she had pulled the floor out from under him, and he fell squarely down on the freshly mopped tiles.

Marina sketched a victorious smile. With a firm tread she strode into Doña Georgina’s bedroom. She filled the room with an aroma of desperate melancholy (she had drawn it from her father’s body) that trampled the sheets and dressers.

She was going to kill that old woman with pure frustration. Calmly she went to her room, bundled her things together, and gazed around the mansion. That pest, the Velazquez boy, lay on the floor in a state from which he would never fully recover. The master bedroom smelled of stale dreams that accelerated the palpitations of the heart. The whole house gave off disconnected, nonsensical aromas, so that nobody in town ever wanted to visit the Velazquez house again.

Marina smiled. Now she would go see Eladio. She would go resuscitate the Pinchimoja. She would leave that house forever. But before exiting through the front door a few filthy words –which surprised even her– escaped from her mouth. Walking down the balcony stairs, she was heard to say with determination,

“Let them say now that blacks stink!”

Commentary

This story reminds me of the book by the Chilean American born in Peru, Isabel Allende, As Water for Chocolate. The difference is that Puerto Rican Mayra Santos-Febres gives it another dimension. Marina's character somehow evokes the feminine instinct to create and desire freely.

However, before we explore how religious and political systems redesigned women and minorities' roles to fit into the plan of modernity, I must introduce the fantastic storyteller that gave voice to today’s cuento, story.

Diane Macklin has dedicated over two decades to the art of storytelling and listening. She engages audiences with a dynamic, theatrical style, blending in her background as a certified educator, dancer, and cultural mediator. She has performed from Massachusetts to California in many different venues and festivals.

She is the 2018 winner of the Jackie Torrence Tall Tale Contest for the National Association of Black Storytellers’ Festival and Conference.

Diane lives as a narrative enthusiast and writer, fully invested in the ancient power of storytelling to transform; heal; and explore the unique, yet universal elements of humanity. As a performer, workshop presenter, keynote speaker, and teaching artist, Diane aims to “Make a Difference, One Story at a Time!” http://www.dianemacklin.com/

*

If you like the program, consider subscribing to the podcast by visiting our website www.trescuentos.com or in any podcast app you use to listen to your favorite shows.

If you have a topic or an author you would like us to consider for future programs, contact us through our website.

Last, suppose you find value in what we are doing here at Tres Cuentos. In that case, we appreciate your positive comments on iTunes, and of course, share the episodes.

And here I must give a shout out to one of our listeners, Hugh Robertson. Mr. Robertson wrote us a very thoughtful reflection on the stories that we tell repeatedly and that we rarely question. So, muchas gracias Hugh Robertson for taking the time to write to us.

(About the author)

But it is time to talk about the marvelous woman that wrote today's cuento, Mayra Santos-Febres.

The National Foundation for Popular Culture of Puerto Rico's website tells us that the vocation of Mayra Santos-Febres is summed up in what she says, "Give me words and I do anything with them."

Santos-Febres is a writer, professor, and poet. Like my mother did for me, Santos-Febres' mother instilled in her a love of literature.

The National Foundation for the Popular Culture of Puerto Rico tells us an anecdote about Santos-Febres' childhood. "From a young age, she showed an interest in the world of lyrics. She kept a notebook where she wrote poetry. But the one that motivated Mayra to have a career in literature was her seventh-grade Spanish teacher, Ivonne Sanavitis. One day, the teacher discovered Mayra writing in her notebook things that were not related to the class. The teacher approached the girl, looked at the writing, and said, look at this, there is potential for a writer here."

Santos-Febres has been called the "the owner of what writer Ana Lydia Vega calls 'hyperconscience', that is, the ability to think critically and beyond social conventions."

The Foundation continues saying that "Mayra is an advocate of just causes, defending those who are marginalized and rejected by society. She is an anti-racism activist. These convictions come to light in her literary works, her short stories, poems, and novels. In her writings, she advocates for the sexual and personal freedom of women, the rights of homosexual and black communities, and the essence of Puerto Rican as Caribbean and Antillean."

Among Santos-Febres’ awards are the Radio Sarandí Award, part of the Juan Rulfo International short story competition, in Paris, France. Her novel Sirena Selena deals with the marginality of transvestites. It has received significant international reception, especially in France and Italy.

But I am not going to tell you anymore because, after the comments, we'll have Mayra Santos-Febres sharing her experience as a Puerto Rican Afra-descendant writer.

(Main Topic)

In the previous episodes on Afro-descendant literature, we talked a little bit about how religion long determined what was acceptable, beautiful, and standard in the Hispanic cosmos.

Therefore, today we will take the train that connects the Catholic religion's colonial ideas to the ideologies of modernity.

So, we must refer to the article written by anthropologist Mara Viveros-Vigoya, "Blanqueamiento social, nación y moralidad en América Latina" (Social whitening, nation, and morality in Latin America).

Anthropologist Mara Viveros-Vigoya reminds us about something we talked about in the previous episode. She says that "In the Latin American colonial context, the legitimization of blood-cleaning – which operated in the Iberian Peninsula and required documenting an ancestry without religious Jews or Muslims stain – gradually became the need to prove that there were no black ancestors (such as mulattos, Zambos, or other colors) visible in the skin tone and physiological traits. At the same time, the same colonial dynamic that created the castes allowed processes of social ascent by the whitening, allowing 'Indians' and 'blacks' to overcome the limits that their condition imposed on them through a process of successive inter-breeds over several generations."

And so, over time, color became a matter of reputation. Quoting Peter Wade, Viveros tells us that "a person could be white if he was publicly considered so."

I remember a conversation with a Dominican man on our way to the National Storytelling Festival in Jonesborough, Tennessee. After realizing that we spoke Spanish, he told me that he also worked on a documentary about his family in addition to telling stories.

He hoped the film would reflect a bit of the Dominican mentality regarding the fear that many had to accept that they had afro blood. After all, most of his family had a lighter skin tone, but Afro traits could be inferred under detailed analysis. I told him that there was also such fear in some of my family members regarding the possible indigenous ancestor. We laughed at the coincidence, recognizing that such fear perhaps multiplies in the memory of many people.

Viveros-Vigoya reminds us that during colonial times "color, like memory, was a moldable category in everyday life, and that it was defined according to the situation."

Remember that Machado de Assis contrasted reality vs. opinion in episode 35, The Bonze's Secret. The Brazilian author said, "if a thing can exist in someone's opinion without existing in reality, or exist in reality without existing in someone's opinion, the conclusion must be that of the two parallel existences, the only one necessary is that of opinion, not of reality, which is merely an additional convenience."

*

And how does color end up gaining so much importance in Latin America?

Unlike in the United States, where colonizers arrived with their families, in Latin America, many men left their women behind. White women were therefore scarce. Besides, contrary to the northern titan, in Latin America it was easier for slaves to buy freedom. These two variables and others found fertile ground in the newly born Latin American societies, thus contributing to the mestizaje (racial mixing).

Additionally, since the social pyramid had the whites on the cusp and the indigenous people and Afros at the base, there was room to ascend in the middle.

With the large number of mestizos growing and reaching wealth, racial status became a determinant for the white elite. So important was the matter of purity of blood that the responsibility ended up falling upon women's shoulders.

Referring to the social agreement that ensured the purity of blood, Viveros-Vigoya tells us that "In this operation it was crucial to control the sexual behavior of the women of the elite, regarded as the agents who could corrupt or stain the family, threatening the purity of blood that largely defined the social position of the elite in the social and racial hierarchy."

Hence, the old excuse of the importance of a woman's innocence and virtue was equivalent to her family's honor.

Indeed, there were many abortions during colonial times, since no pregnancy resulting from a relationship with a lower-ranking man could bring anything good.

Above all, women should contribute to preserving the system that privileged their husbands, brothers, and fathers. As the Spanish saying goes, nadie sabe para quien trabaja, – no one knows who they truly work for.

*

Then, marriage became more relevant in defining social status. It became the institution that connected sexual domination with racial domination and the state with the family.

During colonialism, policies against interracial marriage were defined. Given that in the subconscious of many Latin American nations, there was the ghost of Haitian's black independence, it was necessary not to give in any way hope or power to the colored people.

However, no matter how many rules were established to keep the elite pure and white, the same did not apply to ordinary people.

Quoting Peter Wade, Viveros-Vigoya tells us that "consensual unions were frequent among the common layers of the colonial cities of Mexico, Lima and Santa Fe of Bogota, and seemed to have been accepted as a cultural norm of that group. [Also] female chastity had less value than in the elite. However, marriage was an institution widely valued by the entire population and was a goal to which everyone aspired."

Perhaps due to the high degree of mestizaje and the laxity with which the rules were followed, the colonial authorities resorted to the Inquisition.

Viveros-Vigoya states that "The Spanish and Portuguese colonizers linked sexual immorality to paganism and pursued witchcraft, not only as heresy but also as a highly sexualized sphere."

In fact, if you look at the Spanish manual used by the Inquisition courts in Mexico and Lima in 1569, and then in Cartagena de Indias in 1610, many of the cases were related to sexuality. I am attaching the link to the PDF document in the biography of the transcript.

Let us continue with the Inquisition's obsession with mestizaje and sexuality.

Viveros-Vigoya cites Luiz Mott's research in Brazil, noting that "many of the sacrileges investigated by the inquisition in Brazil had sexual content."

But Brazil was not the only one under strict scrutiny. Viveros-Vigoya quotes Jaime Borja, a scholar who tells us about the Colombian case by saying that "the sexuality of black, indigenous and mestizo populations was subjected to stricter scrutiny. Thus, racialized populations (people of color) were assumed to commit sins of cohabitation, adultery, and sodomy. Also, witchcraft was linked to prostitution and sexually licentious behaviors."

So, the lives of minorities were examined with a magnifying glass, judged harshly, and even taken out of proportion, especially during the witch-hunting season. While the white elites were given a pass under the old Spanish el peca y reza, empata, if you sin and pray it all goes away!

But do not worry, the church's efforts to reach every individual and social group failed, and thus spaces for freedom and autonomy sprang.

*

It is time to cross the bridge that takes us from the Inquisition to modernity.

We will explore how the project to consolidate and modernize nation states gave women and minorities false hope. Thus, the dream of improving their status and freeing themselves from religious and social scrutiny did not appear.

With the arrival of the twentieth century across Latin America, improving the race became a focal point in national campaigns. Hygienist policies, eugenic programs (or racial selection), urban development, access to education, and modernity were welcomed.

Viveros-Vigoya tells us that in the Colombian case, "The family was the focus of the remedial and formative strategies undertaken to reform the population. Women were considered responsible for reforming/raising the children of the homeland to consolidate a new strong and vigorous nation."

This reminds me of Nazi, communist, and capitalist discourses about the tremendous responsibility that lies on women: the commitment of raising families and, therefore, a nation.

Consequently, manuals for good-manners and domestic-life were designed to guide women in their future obligations as the mothers of modern society.

Viveros-Vigoya states that "each task according to their stage of life was delimited. That includes their roles as mothers, the ideal age to marry, start sex life and have children."

Hence, single women turning thirty were distressed if they had not found a husband. As the old Spanish saying goes, se quedaría para vestir santos, she would end up dressing saints, referring to nuns. Also, it was likely that the spinster would be considered an individual who contributed less to society.

If, in previous centuries, women were only a means for family reproduction or bodies that served for male entertainment, they were now seen as responsible for the national progress. But do not believe the story so quickly. The apparent ascension of women’s status or social role comes with a catch.

The woman was now recognized as in charge of the home economy, creating a cozy nest for her husband. A warm, clean, and organized home undoubtedly would ensure that the husband was kept away from the vices of gambling, alcohol, and street women. Consequently, the man could become a working specimen of the tremendous productive system of modernity.

Sadly, the belief that a good woman knows how to keep her husband happy has not vanished. I have heard from older women and men how important a woman is in her family’s success – often working against her own aspirations.

Viveros-Vigoya tells us that "Women were seen and represented by medical discourse not only as biological mothers but also as moral mothers of children, family, society and the nation."

A study by Donna Guy (1991) in Argentina (quoted by Viveros) refers "to the participation of feminist women in the definition of motherhood, accepted as a destination to be fulfilled by the modern women."

Donna Guy goes on to say that "feminist writers like Raquel Camaña linked motherhood to democracy and raised the centrality of the project of a vital democracy, anchored in the family."

Remember the sarcastic words of the Argentinean writer Alfonsina Storni in episode 30, Dairy of a girl-good-for-nothing, "This morning when I woke up, I remembered that someone said that a fulfilled man should, in life, have a child, plant a tree, and write a book."

I wonder if these tasks are still requisites for achieving happiness; what do you think dear listener?

*

And what does all this have to do with social and racial minorities?

This whole tale of the vital female role in building a modern nation was part of hygienist policies. Such policies were supported by the currents of positivism (where scientific knowledge is above all), social Darwinism (the application of natural selection in human societies), and forensic anthropology, which reinforced the idea of "dangerous social classes."

It was believed that such a population degenerated society and thus should be feared, re-educated, or eradicated. These included those suffering from tuberculosis, syphilis, alcoholism, prostitutes, bums, beggars, and criminals as well as seditious people, and racial minorities.

The sexuality of these groups was a source of mistrust. For Latin American leading classes, people of indigenous or African origin were an impediment to national development.

I have often heard educated people say that indigenous people or Afro-descendant groups that continue traditional practices are backward because they do not want to educate themselves or keep with the times or do not accept state efforts to instill "progress."

This same “progress” today has brought irreversible environmental problems, the extinction of fauna, flora, ancestral people, and languages.

The same progress that overwhelms us with jobs of more than 40 hours a week, sells us junk food, numbs us in front of the TV for hours, and drowns us in bank loans. This same progress that delays the retirement age and encourages us to spend more on things making us desire more than what we need. As my husband nicely put it "it gets to the point that your self-worth is linked to your job productivity."

My dad once said, "mija, the only way to build anything is to ask for a loan." I was terrified; I am afraid of debt. Then I realized that he was somewhat right; that is how the system was designed so that we're always in-debt to it.

Then, under the banner of progress, the republican political culture centered its discourse around working men's dignity and civil rights. And this hardworking man was allowed to exercise his patriarchal authority at home as long as he fulfilled his public responsibilities. In some cases that included the occasional domestic violence and hanging out with his buddies or lady friends when he wanted.

Viveros-Vigoya says that such power to men was granted "through the control of women's sexuality, within the framework of a vigorous but civilized masculinity."

However, the modern nation's patriarchal pact - a mutation of colonial religious forms - based on family values contradicts itself. Viveros-Vigoya states that "while [the pact] sought more flexible race relations, it also sought to exercise strong control of the moral laxity attributed to racialized groups, through policies and programs of social intervention. And while promoting the values of modernity, the pact safeguarded women from them."

In other words, though elevated to the pedestal of being the axis of the family and therefore of the nation, women were always suspicious and considered incompetent.

Ask yourself why for so long, positions of power were occupied solely by men. Many times, I heard older women consider themselves less intelligent. Only their offspring and their husbands have the brains that the poor-lady believe did not inherit.

Ultimately the beneficiaries of modernity were only heterosexual white men from a good family.

Now, I do not intend to rise in anger against those who have benefited from the old ways. They probably do not even know how they got there. Entitlement is also rooted in ignorance. The problem lies in what we assume is right, in the stories and prayers that we repeat as creeds without questioning whose agenda they support.

For there to be a wealthy top 1%, there must be 99% who carry them on their shoulders. Suppose we, the 99%, begin to shake off the ideologies inherited from our families and societies. In that case, we may be able to unplug ourselves from the matrix.

My parents instilled in me the virtues of skepticism. My dad said not to follow others blindly, think for myself, and question what others wanted.

My mom still warns me to suspect passionate speeches because there's always something else.

Let's remember the short story with which we began the episode "Revenge of the Mermaids." In it, Mayra Santos-Febres warn us about that old belief that sirens by sheer evil caused the ruin of men. Instead, she suggests that perhaps the old version is just a poorly told tale.

Without further ado, it is time to present the interview with Puerto Rican author Mayra Santos-Febres. In the interview, the author reminds us of the need to reassess and question the inherited forms of models that no longer serve us.

(Interview)

Transcript pending

(Last story or poem)

Before we conclude the episode, I will leave you with another poem by Mayra Santos Febres.

Website: SX Salon.

Poems by Mayra Santos Febres. Translated by Vanessa Pérez-Rosario. URL: http://smallaxe.net/sxsalon/poetry-prose/poems-mayra-santos-febres

air is lacking,

wanting

so the journey goes on

to the illegitimate city in the ocean’s deep.

undocumented alveoli

explode in melancholy song,

air is lacking

but what’s different on the surface

if on the surface everything else is wanting

everything for the cooking pot and for the breast

for the pocket and the eyes

cold and calloused from walking so

and waiting

air is lacking,

wanting,

still wanting.

a few lights glisten among the algae.

maybe in the ocean’s deep there is an excess

of everything that suffocates here.

Farewell

And that's all for today. Remember to share the episodes and write us a nice email through our website www.trescuentos.com.

Spoiler alert the next season has to do with imagining the future. Yes, ladies and gentlemen, we will return with the beginnings of Science Fiction in Latin America. Until the next cuento, or story, adiós, adiós.

Bibliography

Urban Oracles: stories by Mayra Santos Febres, translated by Nathan Budoff &Lydia Platon Lázaro. Copyright © 1997 by Brookline Books, Inc. Used with permission of translator Nathan Budoff. All rights reserved.

Afro-Puerto Ricans in the Short Story, An Anthology. Edited by Victor C. Simpson. Copyright © Peter Lang Publishers, Inc. New York.

Boat People. Mayra Santos Febres. Publicado por Ediciones Callejón, 2005.

Article: Blanqueamiento social, nación y moralidad en América Latina. Mara Viveros Vigoya. URL: http://books.scielo.org/id/mg3c9/pdf/messeder-9788523218669-02.pdf

Website: Círculo de poesía (Digital Magazine of Literature) https://circulodepoesia.com/2010/11/microcuentos-de-mayra-santos/

Website: SX Salon. Poems by Mayra Santos Febres. Translated by Vanessa Pérez-Rosario. URL: http://smallaxe.net/sxsalon/poetry-prose/poems-mayra-santos-febres

Credits

Gnarled Situation by Kevin MacLeod is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Source: http://incompetech.com/music/royalty-free/index.html?isrc=USUAN1100405 Artist: http://incompetech.com/

Hit the Streets (Version 2) by Kevin MacLeod is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Source: http://incompetech.com/music/royalty-free/index.html?isrc=USUAN1100882 Artist: http://incompetech.com/

Gaviota - Quincas Moreira

El Gavilan - Quincas Moreira

Amor Chiquito - Quincas Moreira

Love or Lust - Quincas Moreira

The Black Cat - Aaron Kenny

Sonora - Quincas Moreira

Friday Fugue - Trevor Garrod

Comments